5 Offseason Training Mistakes That Are Keeping Your High School Athletes Slow, Small, and Weak

Sports Performance | Strength & ConditioningABOUT THE AUTHOR

Andy Baker

With over 15 years of dedicated experience as a personal trainer and strength coach, Andy Baker is one of the most sought after strength and fitness experts in the industry. Andy is a certified Starting Strength Coach, and owner of Kingwood Strength and Conditioning, a Starting Strength Certified Gym.

Andy is the co-author of Practical Programming for Strength Training, and The Barbell Prescription.

Andy has provided strength & conditioning coaching to hundreds of elite athletes, as well as high achieving adult fitness clients who want to change their lives through his methods. Andy writes regularly on his website – AndyBaker.com.

As a strength coach in private practice I’ve had the unfortunate experience of looking at some of the “offseason” training plans that many of my student-athletes have brought home with them over the summer. With the supposed goal of building strength and muscle mass in the offseason, most of these plans accomplish neither one with much success.

If they’ve trained with me before, most of the kids hand me the “training plan” their “strength coach” printed out for them before they left for the summer and just kinda roll their eyes. I do too. If they’ve done real barbell training before, they know the plan on that sheet of paper is largely a bunch of BS.

The problem with most of these offseason training plans (at both the high school and collegiate level) is that they seem to be a mish-mashed odd mixture of “sport-specific functional training” exercises and a bodybuilding routine out of FLEX magazine. Too much isolation work, too many exercises overall, and a lack of emphasis on the foundational barbell exercises. Oh and don’t forget conditioning. Lots and lots and lots of conditioning.

So for the young growing athlete, who still lacks a basic foundation of strength and muscle mass, I can’t think of a worse approach to offseason training.

I’ve been training collegiate and high school athletes since 2001. In the last 15 years, I’ve seen a lot of trends come and go in the Universities and the High Schools in the state of Texas. Some good trends, but mostly bad, and a few that just won’t go away.

For the purposes of this article, we’ll focus on common mistakes that strength coaches and sport coaches make at the high school level during their offseason programming.

// Mistake #1: Replicating Collegiate and Professional Programs

Mistakenly many athletes, parents, and coaches believe that the higher level the athlete the better their training plan must be. It’s actually been my experience that the inverse is often true. This flawed line of thinking mainly has to do with a failure to recognize just who is playing at the various levels of sport. And it has everything to do with genetics. At the top of the food chain, let’s take the NFL or major Division I college football programs for example, strength coaches are working with the absolute pinnacle pool of natural athletes and genetic freaks. Athletes that have made it to this level of sport have come through a distillation process that has winnowed out the weak, the slow, and the small.

I do not in any way discount the amount of work that it takes to become a professional athlete in any major sporting organization. However, I would look to counter the myth (maybe the biggest myth in all of sports) that you can simply work your way into elite athletics through sheer grit and determination. Cornerbacks that run 4.3 40-yd dashes weren’t running 5.2 40-yd dashes in high school. These guys are born great natural athletes – strong, fast, and explosive literally from birth. As much as some strength coaches would like to take credit for a stable of athletes running sub 4.5 40s, no training program in the world can create that kind of speed. Those types of athletes were not created in the weight room.

So what’s the point of saying all this?

At the high school level we aren’t working with the genetically elite athlete, and we need to understand this when we look at program design at the high school level. Sure, we’ll have a few pass through the program over the years, but we need to recognize that the vast majority of high school athletes we are going to work with are completely genetically average. We can’t create a Jadeveon Clowney in the weight room. That kind of rare combination of size, speed, quickness, strength, and power is a God-given ability sewn into his genetic code. Replicating his training program, or his university’s training program isn’t going to yield a team full of Jadeveon Clowneys.

But still, there is an alarming trend to try and replicate what is being done at the collegiate or professional ranks with high school athletes. This behavior fails to recognize that the needs of a genetically average high school athlete are completely different than the needs of a genetically gifted collegiate or pro-athlete.

In most cases, these athletes are already big enough, strong enough, quick enough, fast enough, and powerful enough to compete at the highest level of sport. Or else they wouldn’t be there.

.png?width=640&name=baker-quote%20(5).png)

As strength coaches that work with high school athletes, all we can do is take a very average group of athletes that happen to join our teams or our gyms and make them as big and strong as possible. Size and strength is where we can affect the most change with our athletes. These attributes are highly trainable and severely lacking in most high school kids. Speed, quickness, and power are far less trainable qualities. And to the extent that these qualities are trainable at all, improvements in these areas are largely a function of improvements in strength. Strength being the foundation of all other athletic qualities, this is where our focus must be.

But unfortunately, in a lot of high school programs, it’s not. Coaches spend as much time on SAQ (speed, agility, and quickness) as they do in the Squat Rack. Big mistake. If you want to do Plyometrics and Box Jumps with your athletes, fine.

But you need to understand that improvements in his 40 and his Vertical Jump won’t be nearly as significant if you’d take his Squat from 225 to 405.

So, knowing that size and strength should be the primary focus of our offseason training programs, how do we best go about accomplishing these two objectives with our athletes?

// Mistake #2: Using Too Many Exercises

None of us have as much time as we’d like to have with our high school athletes in the weight room. For coaches employed by their high schools there is the unique challenge of trying to put a large group of kids (often 50 or more) through a productive workout in an hour or so, or sometimes as little as 45-50 minutes. That isn’t a big window of time to get a lot done. So stop trying to cram in 8-10 exercises into that small window of time. All that does is guarantee that everything gets done half-assed. When I look at what most high school strength programs are trying to accomplish in a 1-hour window, I think most of them would be better to just randomly scrap about 60% of their routines and focus on what’s left.

I see it all the time – a lower body day that includes Cleans, Squats, Front Squats, a lunge variation, glute ham raises, and a couple of abdominal movements. Kids are rushed as fast as possible through each exercise so that they can complete the whole workout in a 45 minute window. Minimal rest is taken between sets and yet the kid is expected to get stronger. Rest time between sets is seen as wasted time or laziness. But unfortunately, rest time between sets is necessary for maximal loads to be handled in good form. And maximal loads in good form are required for strength to develop.

I’d rather see this program narrowed down to 5 sets of Cleans and 5 sets of Squats with full rest times allotted to the athlete between sets. I guarantee he’ll get more from the workout than the athlete who frantically sprinted through 6-7 exercises just to try and get everything in.

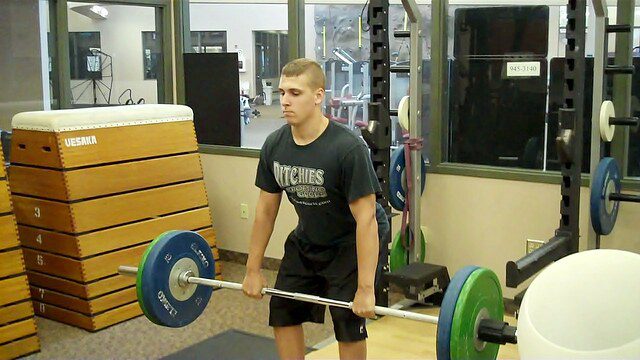

Just focus on the stuff that yields the biggest results – Squats, Presses, and Pulls. That’s it. Most of our athletes should live and die in the Squat Rack. They need to Bench and they need to press weight overhead standing on two feet. And they need to pull from the floor with Deadlifts and Cleans.

These are the exercises that have the most carryover to sport, train the entire muscular-skeletal system of the athlete, and allow them to handle the most weight on a regular basis.

Stop spending 20 minutes of every 60 minute workout on silly “core training” exercises. Heavy Squats, heavy overhead presses, and heavy deadlifts give them all the “core” training they need.

These basic barbell exercises have a learning curve to them and they take time for the athlete to master. As coaches we only have time to teach these kids so many skills. If we are trying to teach our athletes 101 different variations of the squat, we are spreading ourselves and our athletes way too thin, and they’ll never master the basics. This is the same approach we take in any other sport – master the basic fundamentals first. Become flawless in the execution of the basic Squat, Press, and Deadlift. Only when these few exercises are technically mastered and trained to their fullest potential should we consider adding in new or more complex exercises to the program.

// Mistake #3: Trying To Be “Sport Specific” In The Weight Room

This is a term that floats around our industry all too commonly. I wish it would go away because it leads to a lot of very bad strength programming.

First of all it’s critical to understand that strength is not specific. Strength is a general adaptation that can be applied to any specific activity. There is not a football strength, or a baseball strength, or a basketball strength. There is just strength.

And if you are strong, you can do a number of things better than if you are weak. Stronger athletes run faster, jump higher, throw farther, and change direction easier than do weaker athletes. And that is true across all sports.

The best way to exemplify this is to look at the effects of performance enhancing drugs on athletes in wide variety of sports (no I am not advocating PEDs – only using them for illustrative purposes).

We know that at the highest levels of track and field PEDs (specifically anabolic steroids) have been common for decades. Why? Well we all kinda know why – steroids make you stronger and more strength equals more speed. In the 2000s there was a wave of anabolic steroid use in professional baseball that caused some very inflated home run numbers across the entire league. Without naming names, we know who these guys were.

So the question is this – do the track and field athletes and the baseball players take steroids specific to their sport? No. That doesn’t even exist. They all took the same stuff. And it had the same very general effect of producing more strength. And the very general effect of more strength leads to faster 100 meter sprints and more power at the plate. So the very general effect of more strength is simply converted into better performance at any specific skill.

It’s not as if the baseball player took “baseball steroids” and the track athlete took “track steroids.” It almost sounds humorous when you present the argument like this, I know. But it makes a point that many coaches don’t seem to quite understand – there is no such thing as sport specific strength. There is only strength. And there are efficient means of building strength and mass, and there are inefficient means of building strength and mass.

So the goal in the weight room should be to make every athlete as strong as possible in a very general sense. And again, it goes back to my recommendation from earlier about a focus on a very narrow range of exercises – Squats, Presses, and Pulls – preferably all performed with a barbell. These are the exercises we know lead to the greatest general strength adaptation.

Need to sprint faster – Squat.

Need to jump higher – Squat.

Need to explode out of a 3-point stance – Squat.

Need to push off the mound harder – Squat.

Yet we see again and again coaches talk about a need for “sport specific strength.” Do we honestly think that a One-Legged Split Squat on a Bosu Ball is going to lead to more force production capacity than building up a kid’s Back Squat to 405 x 5?

Do we think that a One Arm Dumbbell Press on a Stability Ball is going to build more upper body power than building a kid up to a strict military press of 185 x 5? I’ve even seen swimming programs where kids are trying to replicate the various strokes in the pool against band resistance. Ridiculous.

If you want stronger, bigger, more powerful athletes in any sport, build up their capacity in the basic barbell exercises – Squats, Presses, Deadlifts, and Cleans. Then have them practice and play their sport. That’s it. Trying to replicate very specific movement patterns in the gym is a waste of your time and your athletes’ time.

// Mistake #4: Using Bodybuilding Protocols For Sport

Most of us know that most bodybuilders or physique competitors spend a good deal of time in the higher rep ranges (think 8-15 reps) in order to build bigger more muscular physiques. But it’s important to remember that bodybuilders are not necessarily always training for increased force production. But our high school athletes are. Even when increased mass might be a primary goal of the offseason plan, we need to make sure that strength always remains a focus of the program.

For this reason, I’m not a huge fan of having my athletes train the major core lifts (Squats, Presses, Deadlifts, etc) in the higher rep ranges. I keep the primary lifts usually down below 8 reps, but even more so in the 3-6 range. And I’m not a fan of a high volume of isolation type assistance work for novice athletes either. It contributes much more to soreness and fatigue than it does to strength gains. Better to save that energy for the lifts that count.

There are two main reasons for this. One is force production. More weight on the bar requires the athlete to produce more force, and lower reps per set allow more weight on the bar. Duh. Sets of 10 or 15 reps on the Squat are no doubt hard and will produce some gains in hypertrophy, but they lack any substantial force production component. The weights are simply too light and bar speed gets too slow to call this strength training.

The second reason is the avoidance of inflammation and severe Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness or DOMS. Some athletes and most CrossFitters (a friendly jab!) seem to take pride in the amount of soreness a given workout can generate. But muscle soreness is not a badge of honor. A fool can create sore muscles, and it isn’t an indicator of progress. Very high rep training on exercises like Squats and Deadlifts can produce profound levels of non-productive muscle soreness that bleeds over into every other activity they’ll perform in a given week.

On a well-designed program a novice high school athlete should be able to train the Squat productively 3 times per week. If he or she is creating so much soreness in a workout that an entire week is needed between training sessions, they are losing time where they could be making progress with more frequent training sessions.

But knowing that a relatively high training volume is necessary for growth and gains in muscle mass, I’m much more in favor of a high set count, greater training frequency, and the continual addition of weight on the bar on a weekly basis.

A typical bodybuilding protocol on a “leg day” might begin with Squats for 3 sets of 15 reps. A total of 45 repetitions. If pushed to the limit of weight, 3×15 on a squat is no doubt hard. Even brutally hard. The athlete will barely be able to stumble out of the gym on “Jello Legs” and the soreness might persist for days.

Some coaches and athletes might be thinking “Mission Accomplished! We killed legs today!”

All well and good, but to what affect?

Let’s say our athlete has a 1-rep maximum (1RM) of 300 pounds and was able to use 60% of his 1RM for this workout, so 180-pounds for 3×15 or 45 total repetitions. This represents a total tonnage of 8,100 lbs. Oh, and don’t forget he’ll be sore for 4-5 days, so that’s it for heavy squats this week.

Let’s say our next athlete also has a 1RM of 300 lbs. But instead, he used a more sensible approach to athletic based strength training. Instead of performing all 45 reps in one day with higher rep bodybuilding type training, we spread the workload out over a week. On Monday, Wednesday, and Friday the athlete Squats for 3 sets of 5 reps. On Monday, he’ll use 80% of his 1RM or 240 lbs. He’s able to walk out of the gym tired, but relatively fresh and come back on Wednesday. And on Wednesday he’s capable of 3x5x245 lbs. On Friday he Squats 3x5x250 lbs. All a very reasonable accomplishment for a novice athlete.

At the end of the week, our second lifter has squatted a total tonnage of 11,025 lbs. So who gets bigger? Who gets stronger? My money is on athlete #2.

It’s true, none of his workouts were as hard as the kid who squatted all out for 3 sets of 15 reps on Monday. But hard isn’t the point. He squatted the same volume, with much heavier loads and his overall work output was significantly higher.

For novice high school athletes, focus on a narrow selection of exercises performed multiple times per week (2-3) in the 3-6 rep range. This is a far superior approach to training for mass and strength than traditional bodybuilding protocols.

// Mistake #5: Too Much Conditioning

Our athletes need to be in shape. I won’t dispute that. But the question is – how in shape do our athletes need to be? This is largely dependent on the sport, and the time of year.

For a sport like football, it’s a mistake to try to keep our athletes in peak conditioning all year round. It’s not that peak conditioning is inherently bad – it’s that in order to keep them in peak physical condition all year long will take away from the development of strength and mass.

It’s important to understand that conditioning is a rather transient adaptation. This basically means that we lose it quickly when we aren’t training it and we gain it quickly when we are training it. Unlike strength which might take years or even decades to “peak”, conditioning for most sports is different. For the sake of our discussion, I’m going to leave out of the conversation sports that are almost entirely dependent on conditioning like very long distance running, long distance cycling, or long distance swimming.

For our purposes we’ll be talking about more traditional high school sports like football, baseball, basketball, volleyball, and track & field. Sports that require a well-balanced blend of strength, speed, skill, and conditioning.

For most sports, it’s permissible, and even preferred that athletes be allowed to detrain their conditioning levels a bit in the offseason. This is especially true for high school athletes where increased strength and muscle mass is the primary goal of the offseason. Quite simply it’s near impossible to put 20-30 pounds on a high school kid that is conditioning hard 3-4 times per week. Their metabolisms are already very fast and most of them aren’t eating optimally anyways.

You pile on a 3-4 day per week running protocol on top of inadequate nutrition and a fast metabolism and you’ll be perpetually stuck with athletes that are too small and too weak to perform optimally.

I’m not saying that high school athletes should be allowed to get fat and totally out of shape in the offseason. But there is no reason at all for a high school football player to be doing the same level of conditioning in January as he is in July.

The further our athlete is from his competitive season, the more emphasis there should be in the weight room and less on the track. Conditioning can be maintained adequately by training it just 1 or 2 times per week. More than that and you are eating into his ability to perform and recover from hard and heavy weight training sessions.

As he gets closer to competition, then conditioning can be ramped up a bit to meet the needs of his sport. If an athlete is kept in decent shape through the offseason while he is allowed to get stronger and grow, then he can be worked into peak shape in as little as 4-8 weeks with an increase in conditioning workouts.

As coaches, we also need to make sure that the nature of our conditioning testing and training matches the needs of our sport.

The local high schools in my community are still having their baseball team run a 2-mile conditioning test at the beginning of the season. Why? Unlike strength, which as we discussed is a very general adaptation, conditioning is much more specific to the sport.

Why does a baseball player need to have a great 2-mile time? He doesn’t. And requiring that your baseball team have a great 2-mile run time is cutting into their ability to get bigger and stronger. Would we rather have a baseball team of large, powerful athletes who can drive the ball, steal a base, throw a great fastball or a bunch of small undersized kids who can blaze a great 2-mile run.

I’m surprised that coaches don’t evaluate their own testing procedures more critically, but sadly, in 2016, many still do not.

Are you a better coach after reading this?

More coaches and athletes than ever are reading the TrainHeroic blog, and it’s our mission to support them with useful training & coaching content. If you found this article useful, please take a moment to share it on social media, engage with the author, and link to this article on your own blog or any forums you post on.

Be Your Best,

TrainHeroic Content Team

HEROIC SOCIAL

HEROIC SOCIAL

TRAINING LAB

Access the latest articles, reviews, and case studies from the top strength and conditioning minds in the TH Training Lab