The Ultimate Guide to Using Movement Progressions

Sports Performance | Strength & ConditioningABOUT THE AUTHOR

Rob Van Valkenburgh

Rob Van Valkenburgh joins the TrainHeroic blog with 10 years experience in the strength game. Having coached elite athletes in both the private sector and the Division 1 collegiate setting, Rob believes that strength has to be the foundation of all athletic movement and that athletes of all levels deserve a comprehensive strength program. Rob writes regularly on his own website FootballStrengthCoach.com where here shares short form articles, training tips & programs, and other items related to strength and performance for football.

You spend hours putting together a flawless program. You’ve meticulously taken into account everything from the athlete’s FMS score to their personal performance goals.

Then, the team walks in…

…and you have one guy with a back issue, one guy who was up all night fighting with his girlfriend, one who rolled his ankle playing pick-up basketball, and one who had two mid-term exams that morning and is absolutely smoked.

Time to adapt.

At the end of the day, coaching, in its truest form, is recognizing and adapting to situations in order to optimize the outcome for your athletes.

The best coaches in the world share a common trait: rather than having one set program that every athlete must fit into, they adapt and customize their programming to fit the specific needs of the individual athlete. This customization happens countless times every day.

The way you accomplish this is simple…

First, you have to write every program and coach every session with the mindset that the program is written in pencil, not pen. This allows you to adapt and respond to how each individual reacts to your assessments. With assessments, it is important to remember that everything the athlete does should be considered an evaluation. These can range from intake screenings and measuring perceived or observed exertion levels… all the way to watching how your athletes carry themselves as they walk into the weight room.

Based on these assessments, a coach must be willing to counter by tweaking the program to fit the unique needs of the athlete.

These tweaks are referred to as: Progressions and Regressions.

// Planning For The Individual

One of the aspects that is so great about this profession is we get such a high level of exposure to our athletes. With that exposure comes a great opportunity to build a relationship. Based on the knowledge a coach has about how athletes carry themselves, from body language to how they move – and even their tone of voice – the coach knows how each athlete looks when they are fresh and how they look when they are fatigued.

The ability to manage fatigue through the use of a regression is what allows an athlete to perform at his or her peak when it matters most. Don’t forget, we are training athletes, not weightlifters.

Every athlete moves, lifts, and strains differently. They all have unique tendencies and movement patterns that cause them to have specific needs. Not to mention, almost any seasoned athlete has some nagging injury or limitation. Plus, there are a million external factors that can affect an athlete’s training readiness.

It is important to look at the athlete from a holistic point of view and take into account both physical and emotional stressors when assessing your athlete’s daily readiness to perform the movements you have programmed.

During my time at the collegiate level, we would sit as a staff before every lift or run group and go through the roster to make sure we discussed every athlete in order to ensure three things were happening.

- We were giving our athletes the most effective programming possible as we customized the program to the individual and their unique needs. For example, if an athlete had an issue hitting depth on a squat, we would collaborate as a staff to come up with a corrective exercise strategy.

- Every coach was aware of the plan for each lift we programmed, and they were set with a list of progressions and regressions should an athlete need a modification on the fly. When you have a room full of athletes, it is vital that you enter the training session as prepared as possible.

- Self-evaluation of our program in order to pinpoint areas where we could improve both on a technical coaching side, and more importantly, from a relationship standpoint because we know exactly what is going on with each athlete as an individual.

Of course, as you write a program, you should be armed with a ton of data on each individual athlete. Goal setting, injury history, movement screen, and specific body composition needs are your ammo for putting together their training cycle. But, what is equally important is:

- How you respond when something comes up during a training session

- How you respond when an injury occurs that affects the athlete’s ability to perform what you have programmed

A quality coach will always have a plan for each individual specific to every lift they have programmed.

This plan for progressions and regressions is vital to the effectiveness of a training session. Not only will it allow your athlete to maximize the results they get out of the training session, but it will also allow for a seamless training flow because you will be locked, loaded, and ready for any speed bumps that occur during a lift.

<<RANT>> It is important to mention that your relationship with each athlete is absolutely crucial. As a coach, you have to know what is going on in your athletes’ lives. Not only does this affect their readiness to train, but it also builds rapport and trust because the athlete knows you care about more than wins and losses.

You have to be willing to inject yourself into all aspects of the athletes’ lives. You have to know exactly what is going on with them. The fact is, if you don’t know your athletes on a personal level, you are not their coach. <<RANT OVER>>

// Defining Progression and Regression

Now that we have laid the groundwork, let’s look at exactly what a progression and a regression are and what may cause you to pivot your training and implement one…

- A lifting progression is advancing a movement to increase the technical difficulty in order to elicit a higher training response. In most cases, this will happen with your auxiliary movements where you are looking to decrease the stability of a movement, focus on hypertrophy, or add an external implement that will provide a greater physiological response. A progression can be a great tool for building confidence in an athlete. Most athletes, or at least the ones I know, want to improve and advance. And they want the coach’s recognition because it shows the coach is paying attention to them and seeing their progress.

- A lifting regression is where the coach assigns a different movement which allows the athlete to get a similar training response while training in a way that is appropriate to their developmental level or current training readiness. It also limits the fatigue of a movement if they are in-season. The best coaches in the world are not the ones that have athletes lift the most weight. The best coaches in the world are the ones that provide the most effective program which fits the athletes’ needs and provides the greatest amount of transfer to the field or court. As a coach, you should never have an athlete do something they are not physically ready for. If you programmed a movement the athlete is not prepared for, then it is time to implement a regression.

// Important Notes On Regression

Before we get too far down the line, let’s cover the art of the regression and some practices for communicating with the athlete…

A coach can give an athlete a regression and make it so that the athlete understands why they are getting the regression and how it will benefit them. That’s what makes a coach truly great at what they do. Strength and conditioning is about the mind, body, and soul. You can crush an athlete’s confidence, training willingness, and mindset if you make this feel like a setback.

When giving a regression never do it publicly.

Meet with the athlete before the lift or pull them aside during the session. Explain the honest reason you are changing their program. Show the athlete you care enough to be completely honest with them. But do it in such a way that they feel positive. Eye contact and the words you use are vital. If you are working with young athletes who don’t have a high maturity level or ton of weight room experience, never use the word ‘regression’ – always refer to it as a ‘modification’ or an ‘adjustment’ and let them know you are doing it to maximize their results.

As a coach, in many cases, you have to make decisions on the fly regarding whether or not to regress an athlete. When coaching a group of athletes, there should be a decision made on each movement and its effectiveness for each athlete you are coaching. This can happen before the lift, during the warm up, or even a couple of sets into the primary movement. So, here are some examples of situations when you may want to implement a regression.

Example rational for regression:

- Squats are programmed for that day; however, the athlete is having a hard time hitting proper depth.

- During your intake screening, an athlete shows limited range of motion in the hips.

- A push press is programmed, but the athlete has been experiencing shoulder pain.

- A power clean is scheduled, but the athlete’s CNS is taxed.

// Progressions and Regressions For 6 Movement Types

When programming for my athletes, I break each movement into one of six movement types. This allows me to analyze my programs and ensure I am programming with a symmetrical approach.

- For the upper body, the movements are broken down into push or pull and their movement direction (horizontal or vertical).

- The lower body is more straightforward; we just define the movements as either a squat or a hip hinge.

We will go over each of the six movement types and break down the areas for assessment, indicators for regression, and recommendations.

You will notice I do not touch on indicators for progression. The reason for this is straightforward: if an athlete shows proficiency in a movement and the coach feels they are ready to progress, then they should progress. Simple as that. Progressions are easy, regressions are not.

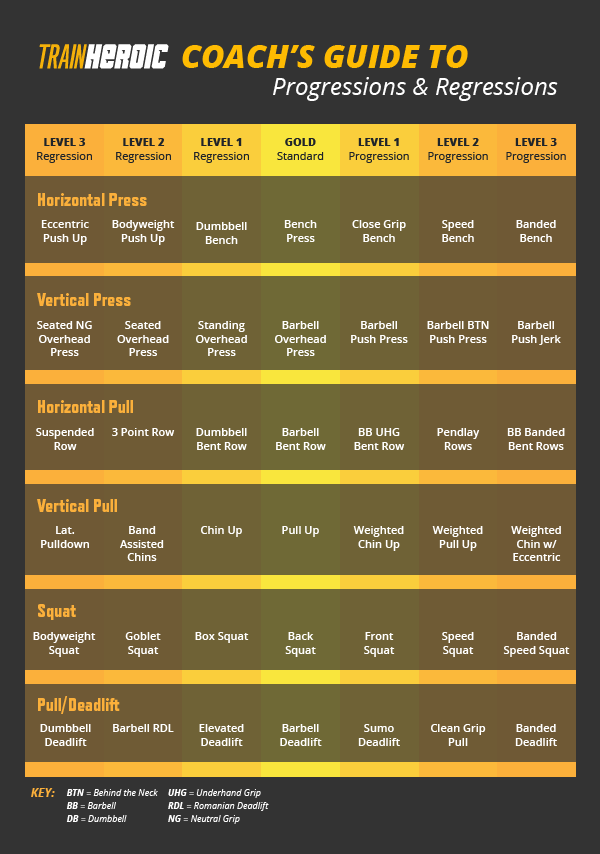

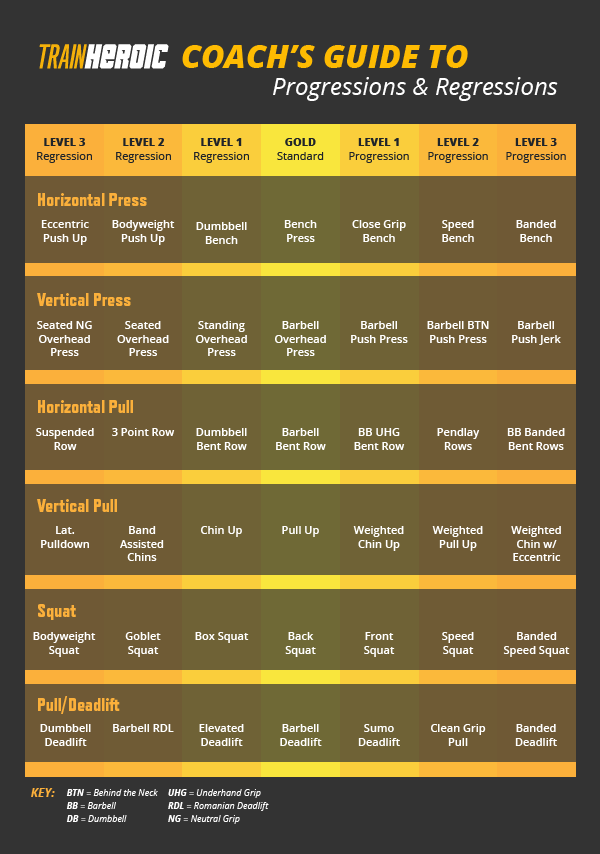

In addition, I have provided my standardized chart for progressions and regressions. This allows me to stay within my select series for exercise selection. Now, is this chart the be-all end-all for every coach? Absolutely not. However, for me, it works based on the qualities I want my athletes to develop and the movements I emphasize within my program.

Your Title Goes Here

Your content goes here. Edit or remove this text inline or in the module Content settings. You can also style every aspect of this content in the module Design settings and even apply custom CSS to this text in the module Advanced settings.

Movement Type #1: Horizontal Press

Movement Objective:

Increase anterior power. Strengthen the prime movers and build stability in the elbow/shoulder capsule. Teach the body to stabilize an external load through an anterior movement in the sagittal plane. Any horizontal press should be performed with a fully braced body that is able to control the weight through a controlled eccentric phase and a smooth transition into a concentric phase. More experienced athletes should focus on the speed of movement during the concentric phase, as the goal with any pressing movement is to develop power.

Primary Joint Movements:

- Concentric Phase: Horizontal Shoulder Adduction, Elbow Extension

- Eccentric Phase: Horizontal Shoulder Abduction, Elbow Flexion

Progression/Regression:

- Level 3 Progression: Speed Bench Press w/ Accommodating Resistance

- Level 2 Progression: Speed Bench Press

- Level 1 Progression: Close Grip Bench Press

- Gold standard movement: Barbell Bench Press

- Level 1 Regression: Dumbbell Bench Press

- Level 2 Regression: Bodyweight Push Up

- Level 3 Regression: Eccentric Bodyweight Push Up (5-1-0 tempo)

Indicators for Regression:

Athlete does not demonstrate the ability to perform the movement in a controlled manner during one or all of the three movement phases – eccentric, isometric, or concentric. In addition to the bar movement, the strength and conditioning coach must watch the athlete’s ability to stay braced in the upper back, torso, and lower body through the entire lift. If the athlete does not possess the neuromuscular control or stability required to produce anterior power through a horizontal press, then the athlete must be regressed to a movement that will develop the prerequisite physical abilities.

Recommendations:

The horizontal press is more complex than it appears and is commonly coached incorrectly. When training athletes, this movement needs to be a total body movement. As such, the athlete needs to be taught how to brace their entire body in order to obtain the results they are training for. In order to do this, the athlete must have a solid strength foundation in their upper back, shoulders, and triceps.

Movement Type #2: Vertical Press

Movement Objective:

Build strength and stability in the shoulders through the pressing of a barbell or dumbbell in the frontal plane. Similar to the horizontal press, the vertical press should be a controlled movement with an emphasis on maintaining a consistent lifting tempo and controlling posture and position in the torso/spine region. Advanced lifters should focus on the speed of movement with more advanced lifts such as the push press and the push jerk.

Primary Joint Movements:

- Concentric Phase: Shoulder Abduction, Shoulder Horizontal Adduction, Elbow Extension, Scapulae Upward Rotation, Scapulae Protraction

- Eccentric Phase: Shoulder Adduction, Shoulder Horizontal Abduction, Elbow Flexion, Scapulae Downward Rotation, Scapulae Retraction

Progression/Regression:

- Level 3 Progression: Barbell Push Jerk

- Level 2 Progression: Barbell Behind the Neck Push Press

- Level 1 Progression: Barbell Push Press

- Gold Standard Movement: Barbell Overhead Press

- Level 1 Regression: Standing Dumbbell Overhead Press

- Level 2 Regression: Seated Dumbbell Overhead Press

- Level 3 Regression: Seated Neutral Grip Dumbbell Overhead Press

Indicators for Regression:

The vertical press is a movement that must be done correctly in order to keep your athletes healthy. There is a compensation pattern that coaches need to look out for. When performing this movement, the athlete must be able to complete the lift with the rib cage locked down which keeps the spine out of an excess lordosis position. If this is noticed, the coach should first attempt to cue the athlete out of the pattern as most athletes will not actually know they are elevating their rib cage and putting their spine into extension. If cuing does not work, a regression is necessary. Other indicators should be discovered during the screening process – poor shoulder mobility and lack of scapula stability. Both of these issues can be corrected with an effective corrective exercise protocol.

Recommendations:

With any vertical pressing movement, the strength and conditioning coach needs to proceed with caution. As with most controversial movements, the vertical press is a great training tool for athletes if coached properly. The issue lies in that coaches are in too much of a rush to get to the gold standard movement and bypass building blocks that garner long-term success. Be patient with overhead pressing and spend time in each level of the movement. The worst thing a coach can do is put an athlete in a loaded overhead position they are not prepared for.

Movement Type #3: Horizontal Pull

Movement Objective:

The horizontal pull is meant to build strength and stability in the upper back, which is paramount in building healthy athletes who have a high capacity for strength gains in pressing movements. As the saying goes – “you can’t shoot a cannon from a row boat.” In this case, the row boat is the upper back and the cannon is anterior pressing movements. The failure to overlook the horizontal pull can result in shoulder impingements and a lack of results in anterior strength movements. When looking at the symmetry of your programming, always ensure that you have a 2:1 ratio of pull movements when compared to push movements. This allows a coach to be positive that they are not overloading the anterior portion of the shoulder. This does two things: first, it keeps the shoulder and surrounding muscles healthy. Then it allows for increased muscle mass in the upper back which builds stability and strength around the shoulder and scapula.

Primary Joint Movements:

- Concentric Phase: Horizontal Shoulder Abduction, Elbow Flexion, Scapulae Retraction

- Eccentric Phase: Horizontal Shoulder Adduction, Elbow Extension, Scapulae Protraction

Progression/Regression:

- Level 3 Progression: Barbell Banded Bent Over Rows

- Level 2 Progression: Barbell Pendlay Rows

- Level 1 Progression: Barbell Underhand Grip Bent Over Row

- Gold Standard Movement: Barbell Bent Over Row

- Level 1 Regression: Dumbbell Bent Over Row

- Level 2 Regression: 3 Point Single Arm Row (hand supported)

- Level 3 Regression: Suspension Row

Indicators for Regression:

As a coach, you want to always be focused on quality of movement. With the horizontal pull, the first thing you should be watching is the control during the concentric phase. Many athletes initiate the movement with the bicep which causes the pull to become more of an arm workout than a true back exercise. If you see this, the first thing is to lighten the weight and cue the athlete to initiate the movement by driving the elbows back instead of pulling the bar or dumbbell to the chest. If the athlete fails to fix the issue, then a regression is needed as the athlete most likely lacks upper back strength to perform the movement properly. Other factors to look for are the loss of neutral spine positioning and a lack of control in the eccentric phase. Both of these can be fixed by spending some time in a regression exercise.

Recommendations:

The upper back responds very well to high volume work which has a great amount of time under tension. If you are starting with a young athlete, focus on building up their back with sets of 12-20 reps on suspension rows, face pulls, band pull apart, and T/Y/W raises. By doing this, you will build a foundation which can be successful when you get into more advanced movements. In addition, the low back and the core play a major role in an athlete’s ability to perform a proper horizontal pull variation. Teach the athlete about trunk stability and attack these areas in your auxiliary or extra needs work if you feel it necessary.

Movement Type #4: Vertical Pull

Movement Objective:

Build strength in the upper back. Perform a bodyweight movement with a high focus on quality and stability in each repetition. Keep the trunk stabilized and avoid swinging of the torso and legs while moving the body with a controlled tempo. With all pulling movements there should be a slight pause at the top of the movement and a high emphasis on performing a controlled eccentric lowering phase.

Primary Joint Movements:

- Concentric Phase: Shoulder Adduction, Shoulder Horizontal Abduction, Elbow Flexion, Scapulae Downward Rotation, Scapulae Retraction

- Eccentric Phase: Shoulder Abduction, Shoulder Horizontal Adduction, Elbow Extension, Scapulae Upward Rotation, Scapulae Protraction

Progression/Regression:

- Level 3 Progression: Weighted Pull Up w/ Slow Eccentric

- Level 2 Progression: Weighted Pull Up

- Level 1 Progression: Weighted Chin Up

- Gold Standard Movement: Bodyweight Pull Up

- Level 1 Regression: Chin Up

- Level 2 Regression: Band Assisted Pull Up OR TRX Pull Up

- Level 3 Regression: Lat. Pulldown

Indicators for Regression:

Athlete cannot perform a minimum of five repetitions of the bodyweight pull up with a high level of technical proficiency. The coach must use his/her judgment to determine the level of regression. In most cases, if an athlete cannot perform a single pull-up, the coach will be best served by going straight to a Level 3 regression and focusing on building volume in the back. They can then follow the regression chart through each training cycle with the goal being to get the athlete to the gold standard movement within 4-5 training cycles.

Recommendations:

The vertical pull movements are one of the hardest movements for an athlete to perform with quality technique. For the majority of athletes, a Level 3 regression may be their starting point. So it is vital to perform some form of pre-training screening process to determine an athlete’s strength in this plane of motion.

Movement Type #5: Squat

Movement Objective:

The squat is a foundational movement every athlete should be able to perform with a very high level of technical proficiency. This movement is arguably the best for improving lower body strength, power, and endurance. In addition, the squat is one of the most powerful exercises for building explosiveness in athletes because it teaches them to apply force into the ground.

Primary Joint Movements:

- Concentric Phase: Hip Extension, Knee Extension, Ankle Plantarflexion

- Eccentric Phase: Hip Flexion, Knee Flexion, Ankle Dorsiflexion

Progression/Regression:

- Level 3 Progression: Speed Squat w/ Accommodating Resistance

- Level 2 Progression: Speed Squat

- Level 1 Progression: Barbell Front Squat

- Gold Standard Movement: Barbell Back Squat

- Level 1 Regression: Barbell Box Squat

- Level 2 Regression: Dumbbell or Kettlebell Goblet Squat

- Level 3 Regression: Bodyweight Squat

Indicators for Regression:

For most athletes new to the weight room, the major concern is two-fold: lack of mobility and lack of trunk stability. As with most movements, a simple pre-training screening test can expose these movement limitations. You can also look at an athlete’s training age and experience in the weight room. If an athlete does not have a large amount of training experience, you may want to go directly to the Level 2 or 3 regression regardless of what their pre-training screening test shows. This will allow you to build an extreme level of competency in the squat movement and allow you to only axial load the athlete when you are completely confident they are ready for it.

Recommendations:

With the squat, patience is key. Most coaches are in a rush to put a bar on an athlete’s back in order to begin working toward large max testing numbers. However, as coaches, our goal should be to build the best athlete possible and that is achieved by ‘slow-cooking’ the athlete’s progressions by not giving an athlete the gold standard movement until you are confident they are prepared for it.

Movement Type #6: Hinge

Movement Objective:

The hinge is a bedrock movement for all athletes. It is one of the most transferable movements to both the athletic arena and other strength exercises. The hinge, which is most commonly associated with the deadlift, trains the posterior chain better than any other strength movement and – as any quality coach will agree – the posterior chain is the building block of athletic performance. When looking to improve an athlete’s performance – whether it is in the vertical jump, sprinting, or other explosive variations of force – hip extensions are the key and the hinge movement should be trained very often.

Primary Joint Movements:

- Concentric Phase: Hip Extension, Knee Extension

- Eccentric Phase: Hip Flexion, Knee Flexion

Progression/Regression:

- Level 3 Progression: Deadlift w/ Accommodating Resistance

- Level 2 Progression: Clean Grip Pull (speed deadlift)

- Level 1 Progression: Sumo Deadlift

- Gold Standard Movement: Traditional Deadlift

- Level 1 Regression: Barbell Elevated Deadlift from Blocks or Pins

- Level 2 Regression: Barbell RDL

- Level 3 Regression: Dumbbell or Kettle Bell Deadlift

Indicators for Regression:

As a coach, the first thing you want to look at is the athlete’s ability to get into a proper starting position. This means the back is braced, the knees are aligned over the toes, and the hips are sitting above the knees. If the athlete cannot get into this position, then a regression and corrective exercise strategy is needed. In the event that the athlete is able to get into a proper starting position, but cannot maintain a braced spine through the full range of motion, then a Level 1 or Level 2 regression will be in order. The Level 3 regression should be limited to introductory athletes or anyone who has an extreme lack of mobility. That said, the Level 3 regression is one of the best teaching tools a coach can use to instruct the athlete on proper lifting technique.

Recommendations:

Pulling from the floor is a movement that every athlete, regardless of sport, should be proficient at. The need for progressions and regressions in the hinge movement is completely based off how well an athlete moves through the range of motion. As you program for the pull movement, make sure that you are programming a large volume of accessory work which will strengthen the hinge. Focus on low back, glutes, and hamstrings. Remember, with your accessory work for the posterior chain, those muscles respond to time under tension, so start with higher rep work to build up a foundation.

// 3 Things To Remember When It Comes To Progressions And Regressions:

- Always have a plan for each athlete. Do this by reviewing your program every day. Take into consideration how each individual will respond to the assigned lifts. If you feel an athlete needs a progression or regression then make the decision and implement it. Remember, do this in a manner that fits each athlete. Know your team as individuals and coach them accordingly.

- If you are giving an athlete a regression, be sure to explain exactly why you are changing their program and provide them with a road map to get them back on track. If the athlete understands why you made the decision, their buy-in will go through the roof. Great coaches are great communicators.

- Never progress an athlete to a movement or lift they are not ready for. Progressions are earned, and if an athlete has not demonstrated mastery of a movement, they should not be progressed.

// Be A Great Coach

What this whole article boils down to is simply being a great coach. Not the type that does the ‘overweight coach power stance’ in the corner with a 32oz coffee and just yells ‘deeper!’…Get in the mix with your athletes. Watch how they move day in and day out. Get to know their bodies, personalities, and body language.

John C. Maxwell had a great acronym for developing relationships: FORM (Family, Occupation, Recreation, and Message). For the context of this article, look at it like this…

- Family: What is the athlete’s life like outside of the weight room. Do they work? Do they look after siblings? What is their home life like?

- Occupation: What is their role on the team and how can you make them better? Do they know that you understand their role and do they believe you can help them increase their athletic potential?

- Recreation: What do they do for fun that may impact their performance in the weight-room? Did they play pickup basketball all day? Are they worn out because they are a multi-sport athlete?

- Message: How you relay the message to them. Do they understand the reason for a regression or progression? Do you do it in private or public? Do they know what the road forward looks like? The importance of this cannot be overstated.

Now that you are armed with a plan for how you will progress and regress your athletes, take this information and implement it. Make sure that your whole staff is aware of the action steps with each individual athlete. Know what to watch for and when you see it, make the change.

Never hesitate to pivot if the need is there.

Now, get in the racks and get after it.

Are you a better coach after reading this?

More coaches and athletes than ever are reading the TrainHeroic blog, and it’s our mission to support them with usefull training & coaching content. If you found this article useful, please take a moment to share it on social media, engage with the author, and link to this article on your own blog or any forums you post on.

Be Your Best,

TrainHeroic Content Team

HEROIC SOCIAL

HEROIC SOCIAL

TRAINING LAB

Access the latest articles, reviews, and case studies from the top strength and conditioning minds in the TH Training Lab